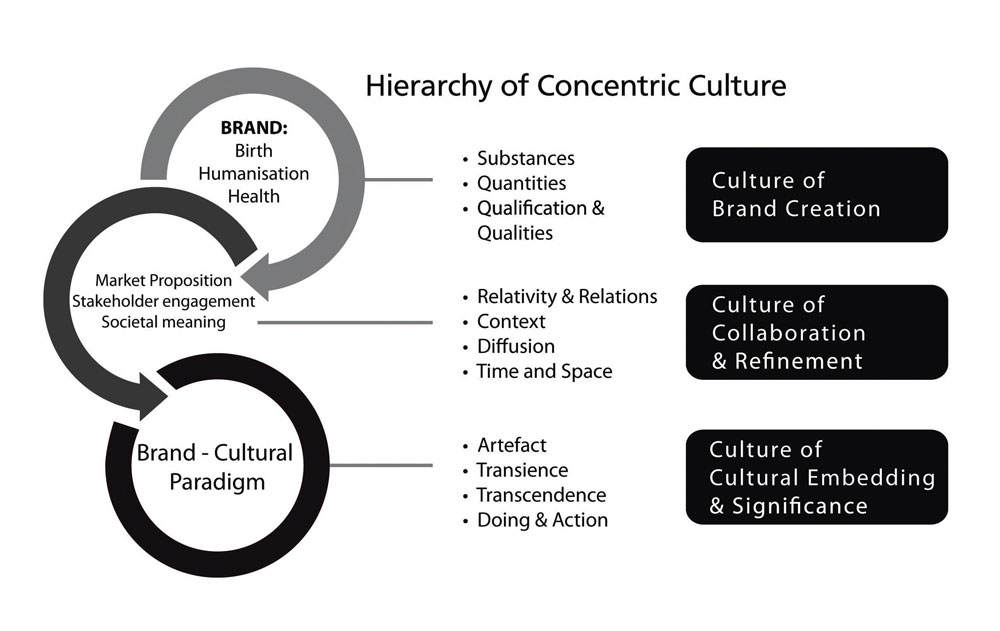

Qualitative investigations, in the form of a 16 month Expert Delphi Study, elicited iterated views from an international panel of academics and practitioners. Findings assert that culture and brands have the ability to influence each other and share strong human relationship bonds and allegorical likenesses. Furthermore, successful brand management requires cultural approach and leaders, who can mediate dynamic and complex networks of brand stakeholder relations. It was concluded that understanding brands, culture and management have to take into account: context, space and time – as porous boundaries of transience and transcendence. A new, grounded theoretical framework for brand management was developed – which took its inspiration from Aristotle’s Praedicamenta.

Lessons from Aristotle

Aristotle’s Categories is a text from Aristotle’s Organon, which places all objects of human apprehension under one of ten categories – known as the praedicamenta. The Categories asserts that all possible kinds of ‘thing’ can be the:

• Subject: A person, thing or circumstance that is being discussed, described, or dealt with – giving rise to a specified feeling, response, or action. It is the central substance or core of a thing as opposed to its attributes – about which the rest of a clause is predicated.

• Predicate of a Proposition: Predicates are the part of a sentence or clause containing a verb and stating something about the subject. Within the rules of logic, this ascribes that something is affirmed or denied concerning an argument of a proposition. Propositions are a statement or assertion that both expresses and demonstrates a judgment or opinion, that logically expresses a concept that can be true or false.

These forms of subject and predication, which are part of Aristotle’s categories, are expanded as follows:

1. Substances: which are those primary and particular things, which cannot be predicated, in comparison to secondary substances, which are universals that can be predicated. Hence, Aristotle, for example, is a primary substance, whilst man is a secondary substance. Therefore, all that is predicated of man is predicated of Aristotle.

2. Quantities: which are discrete or continuous extensions of objects.

3. Qualification or Quality: where their determination characterises the nature of the object, often using adjectives.

4. Relativity or Relations: considers the way in which objects are related to each other, the dependencies of various physical phenomena and their relative motion in connection with the observer – especially regarding their nature and behaviour.

5. Where: maps the position of things in relation to the surrounding environment.

6. When: positions objects in relation to the course of events, according to time.

7. Being-in-a-position: which is a human construct, taken to mean the relative position of the parts of a living object, attributed with a present participle and adverb. Therefore, can be viewed as the end point for the corresponding action – given that the position of the parts is inseparable from the state of rest implied.

8. Having [a state or condition]: indicating that a condition of rest results from an affection – namely, being acted on and, therefore, denoting a past tense. These are physical attributes of objects, which apply both to the living and the inanimate.

9. Doing or Action: which produces change in another object.

10. Being-affected or Affection: here, acting is also to be acted on. Within this category, Aristotle considers this to be a general construct which accommodates passion, passivity and the reception if change from another object.

Bringing Aristotelian thought into branding

Literature searches suggests that traditional brand analysis and approaches focus on an inside out view of brands – by first defining brands and then determining how they perform. More recently over the past ten years, the cultural approach jumps from defining and refining brand thinking, towards expanding it to consider cultural interactions. This is embodied through the ‘bird view’ topdown bottom-up approach advocated. Whilst this approach has yielded some interesting findings, I have attempted to bring forth an additional step, which maps out networks and contexts, through stakeholder analysis. In doing so, this approach advocates an outside-in approach as a starting point.

The difference in this lens of analysis is that it is grounded in four factors:

1. The balance and significance of the brand manager/consumer interplay should be weighted in favour of the consumer

2. Consumerism should be viewed as not being determined just by the purchase of a branded product or service. Rather, brand consumerism is governed by and present in a wider sphere of human existence than the branded product or service. As consumers have amassed such high levels of control, brands can and do exist outside and beyond the objects, services and organisations that they were created for. Brands have become objects in their own right, which gifts them a separate life cycle than that of a product or service. This has meant that they have been used increasingly to create brand extensions, and as words, language, terms and explanations to define modern-day existence. Therefore, defining usage in turn has to accommodate evolutionary intangible, as well as tangible elements

3. The complexity and reality of culture should be considered in tandem with brands. So, rather than a cultural approach to branding, where a brand is an agent and artefact of culture; culture is also an agent and artefact of brands. Therefore, additional meaning and contextualization of culture is advocated and linked to branding

4. Whilst accepting and arguing for brands being treated as human-like entities, their presence enjoys elements of duality. Brands are viewed, treated as, and behave as humans. However, they are also metaphysical philosophical constructs, which bind collective memes together, individuals and objects.

From these assertions, the Brand-Cultural Praedicamenta forms my focal theory and thesis:

Here:

• Culture defines brands

• Culture determines who, where, when, why and how a brand exists

• Brands can drive and define Culture reciprocally

• However, few brands govern culture.

• And as such, most brands are a product of culture.

Culture exists on different levels and serves different purposes at each stage of the process. This means that before a brand-cultural paradigm comes into existence:

• Brand managers, designers and brand creators are cultured

• There is a cultural process employed when creating a brand

• Brands become cultural artefacts and agents

• Marketing a brand is a cultural process

• Humans exist within contextual cultural systems, which brands enter

• Markets, exemplified through brands, create and respond to cultures

• Brand stakeholders are drawn into new dynamic collaborative cultural systems

These then culminate in a brand-cultural paradigm, which signals:

• Cultural innovation and creation

• The sustained existence, relevance and meaning of a brand

Brand managers are guardians of a brand’s essence, heritage and stakeholders. Therefore, a key finding is that whilst consumers may adopt, nurture and influence brands, the initial surrogate and parent of a brand is the brand manager. Based upon this, I posed a polemical argument: if a brand is a human; then when observing how humans comparably succeed or fail, an individual’s ancestral heritage (parents) and upbringing are frequently evaluated for clues. However, literature points towards a paucity of research on the views, experiences and attributes of brand managers – so does this represent a gap in thinking? When considering the humanisation of brands in more detail, findings suggest that defining a brand beyond its ‘biological’ and ‘anatomical’ function is problematic. Following the same train of thought: judging the ‘success’, ‘failure’ and ‘mediocrity’ of an individual in society, based only upon physical attributes, is highly contentious. This is perhaps why later approaches seek to investigate brand personality and relationships in more detail.

However, when cross-referencing these again with human existence, the inference is that better ‘humans’ have more relationships, garner greater loyalty from more people, and possess stronger coherent personalities. I argue that frequency, longevity and volume of relationships; and stronger personalities do not necessarily gift humans, culture and brands critical success factors.

Cultural anthropological approaches argue that there is no ‘better’ or ‘worse’ culture, there just ‘is’. And as such I argue that the same can be said when evaluating brands. It is debateable whether empirical evidence can fully encapsulate what makes a brand better. As an analogy, because branding draws from religious terminology such as ‘icons’, it is suggested that when looking at religions: concepts of deity, observance and spirituality conceptually cannot be ranked and judged as being better of worse than each other – they just ‘are’. And so, Brands ‘are’. They are subject to contextual evaluations, which can position them as being better or worse, but this judgement is linked to the mind of the beholder.

As a further expansion on this treatise, I pose an additional polemical argument, which is: as human relations are more organic, nuanced, subjective, intuitive and impulsive; comparably can brand scales predict future success? Furthermore, ‘bird view’ surface judgements made by those outside of a relationship, if in the absence of detailed understanding, may even view these relationships as being puzzling, or even paradoxical. Evidence for this can be observed where brands are consumed by non-target consumers and viewed in ways not predicted. In addition, irreconcilable cultural differences may yield acceptance, but not necessarily understanding. These observations it can be argued conform with the human existence – in that not all of life is known, can be judged, or predicted.

Findings and discussions suggest that defining brands and culture, and calculating their value are only a starting point and a ‘health-check’, but not a guarantee of their worth and understanding. Instead, more important is an evaluative appraisal of what brands and culture mean to others and where/how/why they ascribe value to them. This means that whilst the laws and processes may be universal: subjective opinions and conclusions may be capricious – and these are facets of human existence. In tandem, comparing cultures can only be achieved to a point. And so, as brands aim to be humanly unique and cultural: a component of their essence will be irreplaceable and perishable.

Therefore, the more humanoid a brand is, along with being more culturally active: then the more successful, transient and transcendent it becomes. These developments and factors have led rise to the brand-cultural phenomenon.

The future landscape for brand managers

Control of this brand-cultural paradigm necessitates that brand managers are actively engaged in the pursuit of cultural professionalism and expertise embedded in societal servitude – where brand managers are able to draw from a broad base of skills and experiences, and have a high degree of peer-acknowledged intellectual aptitude.

The impact on brand managers has been that they have had to become more qualified, both academically and practically, with an increase in cross-disciplinary and transferable subject skills and knowledge. These are alongside managers being in possession of demonstrable active cultural networks: in order to communicate authenticity and to provide a renewable knowledge base, keeping their knowledge and application linked to real-world events.

Future predictions are that branding, as a subject discipline will expand in terms of its remit and it is on the ascendency, due to its efficacy and affects on business and society – which are both commercial and socio-cultural. Furthermore, with this rise, the role of the brand manager and the governance of brands without care and attention may have wider implications on brands, brand managers and stakeholders. For example, brands are seen to influence more that the organisation, product and service offerings – they are also affecting other areas of generalist human behaviour and interactions, such as: education; ethnicity; language; national identity; nations; international relations; religion; and ancient, modern and contemporary history. It is also apparent that collectively, brands and brand managers have the power to shape perceptions of reality, which even have the potential to reverse the most dogmatic of views. Evidence of this most recently can be seen with how branded commodities have been used as part of an engineering process of being able to change historical perceptions. Results found how brand strength that has driven consumerism has removed, weakened, or overturned cultural barriers. Examples of which can be seen with German, Japanese and US brands entering markets where their previous records of political and humanitarian activities have been far than favourable.

With these observations in mind, therefore, brands, branding and brand management are a culture of cultured activity – which now renders them inextricably linked with culture, but more significantly human existence. A key finding and contribution of this study is the argument that culture and management cannot be fully investigated unless brands are also considered – as brands have become conceptually and irreversibly embedded within humans.

Anomalies in human existence and brand performance still poses problems when trying to ascribe meaning and ultimately make future predictions. I am of the opinion that these will never be eradicated fully, as they follow cycles of orthodoxy and heterodoxy – which delivers revolutionary developments that cannot chart the evolution as a linear progression. For example, some technological advancements are rejected in favour of heritage and retro offerings, which after their occurrence are often attributed to incorrect predictions or a facet of human nature. This had led rise in business to the anthropological approach of accepting occurrences as cultural constructs, shaped by the man-made environment, and as intrinsically neither good nor bad, just as they are. This poses challenges in business and management, as commerce exacts that prediction and control, through scientific methods is a core pursuit.

Therefore, the battleground lies in being able to draw from anthropological methods in order to expand control and thus increase the ability to perform scientifically in a rational, rather than an intuitive and emotive sense. However in doing so, a key question is whether this pursuit moves brands and brand management away from a critical success factor – which is that some aspects of the unknown and uncontrollable, in fact, increase control and success.

This article was originally published in BM Regular Issue 01. To get this any many other issues, subscribe to Brandingmag now!