I saw a video recently of a talk given by Rohit Bhargava, a member of Global Strategy & Planning group at Ogilvy. One of the first questions he asked his audience was how many of them worked in marketing. A surge of hands. Next, he asked how many of those thought marketing was making the world a better place. A trickle of hands.

It’s no surprise. For years, marketing has been thought of as a bullhorn through which numberless brands berate consumers with interchangeable messages. American consumers are now exposed to upwards of 5,000 marketing messages a day. But with the growth of social media and its ability to link people together to support social causes, we may be seeing a sustainable shift from a flood of irrelevant calls-to-action to more nuanced messaging in which brands and social challenges share a common cause.

Some brands within major Fortune 500s are learning how to align their business goals with social goals. It makes perfect sense that it can be done: all brands live within a social context and many were created to serve or solve a human need. In an alarming number of instances over recent decades, business and social goals have parted ways. But two leading brands at Johnson & Johnson and Unilever are bringing these goals back together. After all, the definition of ‘profit’ has never been exclusively financial. A brand can profit by selling product, but that doesn’t mean a society can’t profit when it does.

The Case for Social Relevance

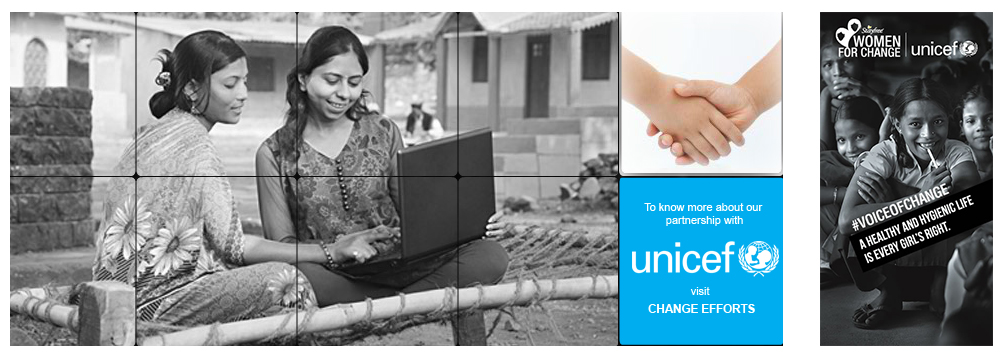

Stayfree, a tampon brand from my agency’s client Johnson & Johnson, recognized in its India market not simply that young women often continued to use unsanitary cloth instead of pads, but that young girls were missing considerable school time due to related infections. They partnered with UNICEF to launch an educational campaign—Women for Change—designed to promote the hygienic advantages of tampon usage and supporting local school-based educational efforts, such as the “Kishori” Programme, which is reaching 7,000,000 girls in 729 schools across the Indian subcontinent. Results? Awareness rose, infections dropped, and girls missed less class. Sure, Stayfree moved product, but it had done well by addressing a genuine consumer need. It knew its audience.

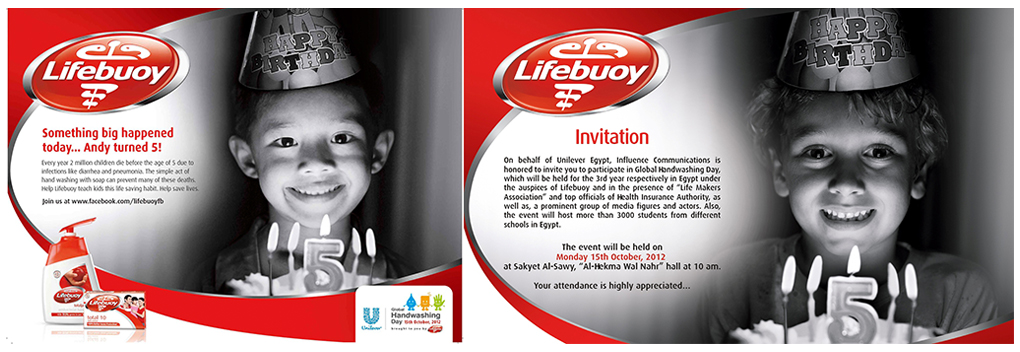

Unilever’s Lifebuoy soap has taken a similar step, as chronicled in a post on HBR.com, aligning its business goals with social goals, namely the Millennium Development Goal 4 of reducing the global number of children that die before they turn five. Investigating their markets, Lifebuoy discovered that two million children around the world die before their fifth birthday because of diarrhea and pneumonia, two potentially fatal conditions that can be drastically reduced in frequency by the simple act of handwashing. Unilever paired with its competition and an organization committed to hygiene to create and evangelize Global Handwashing Day. Since the day was created five years ago, Lifebuoy has doubled its market cap and—much more critically—infant and child deaths from diarrhea has dropped by more than half.

A Three-Step Approach

Both of these projects are examples of the power of content marketing as a tool for social change—but are also examples of smart branding. Adhering to a few simple principles, more brands could produce programs with similarly positive results. A basic approach would include the following:

1) Understand your context: In our socialized environment, it is increasingly critical for a brand to understand the context of its target consumer. What are the life challenges your audience faces and is there a way for your brand to support those challenges? Stayfree, by understanding the life context of Indian girls, was able to support transformative cultural change. Instead of being just another sanitary product on a cluttered shelf, it is part of a movement toward better adolescent health and hygiene.

2) Find a committed partner: When it comes to evangelizing a cause, two voices trumps one. In both examples cited above, the brand found a partner with an inbuilt commitment to its adopted cause. In some cases, an NGO. In others, a competitive set. In either case, the brand’s business goals aligned with those of its partner.

3) Lead from behind: It may sound paradoxical, but a key component in the success of both campaigns was the fact that the brand removed itself from the spotlight. In reality, both Stayfree and Lifebuoy created the platforms that led to social change. But in a marketplace dominated by chest-thumping corporations, these brands chose to place an issue front and center, and simply trust consumers to recognize their contribution to social wellness. It worked. Consumers saw the brand as humble instead of arrogant, helpful instead of troublesome, and patient instead of pushy. As a result, their bottom lines benefited.

From Corporate to Social Capitalism?

Isn’t it time for corporate responsibility to make the shift to social capitalism? Given the increasing costs of bad behavior—for the environment, for global populations struggling to cope with the caprice of a globalizing economy—shouldn’t the Stayfree and Lifebuoy examples serve as a mandate to businesses, rather than simply an admirable model? It’s no longer enough to mine the whimsical desires of a target audience—preference does not a profile make. Scott Goodson, founder of global agency StrawberryFrog and pioneer of movement marketing, has suggested that modern marketing is less about appealing to individuals, and more about appealing to groups, and less about persuading than aligning with existing beliefs. To that end, couldn’t our consumer insights expand to include the collective challenges of a target community, rather than simply a discrete persona within it? That—the latent social opportunity at the heart of every consumer community—can form the foundation of a profitable business strategy.

Full Disclosure: Stayfree is a Johnson & Johnson product, and I do work on Johnson & Johnson brands, but not Stayfree and not this campaign.